[Intro]

The first piece this month, on sight bias, is an example of why I created this newsletter: an idea that has been flitting around my brain for a few years that I pushed myself to build a more fully-formed opinion on this month.

Many of you reacted to the piece last month on housing and homelessness. I have included an additional selection of interesting pieces extending that topic.

And, as usual, there are 5 more things at the end from my ramblings this month.

[What I’m thinking about]

COVID-19 and Sensory Bias Towards Sight

During the peak of COVID lockdowns, I remember listening to a podcast that talked about dogs that were being trained to detect COVID by smelling it in people. Access to COVID testing, especially self-administered rapid tests, was still scarce. The podcast posited that dogs used in this way could be the solution to mass regular testing in places like schools and could lead to their ability to reopen.

And that was the last I heard of the COVID-detecting dog for a while. Schools remained closed for many months after that and, as other forms of testing become available, I began to be regularly required to take expensive COVID antigen tests to do things in daily life. More than 2 years later, I have never been sniffed by, nor so much as seen, a COVID testing dog. What happened to the dogs?

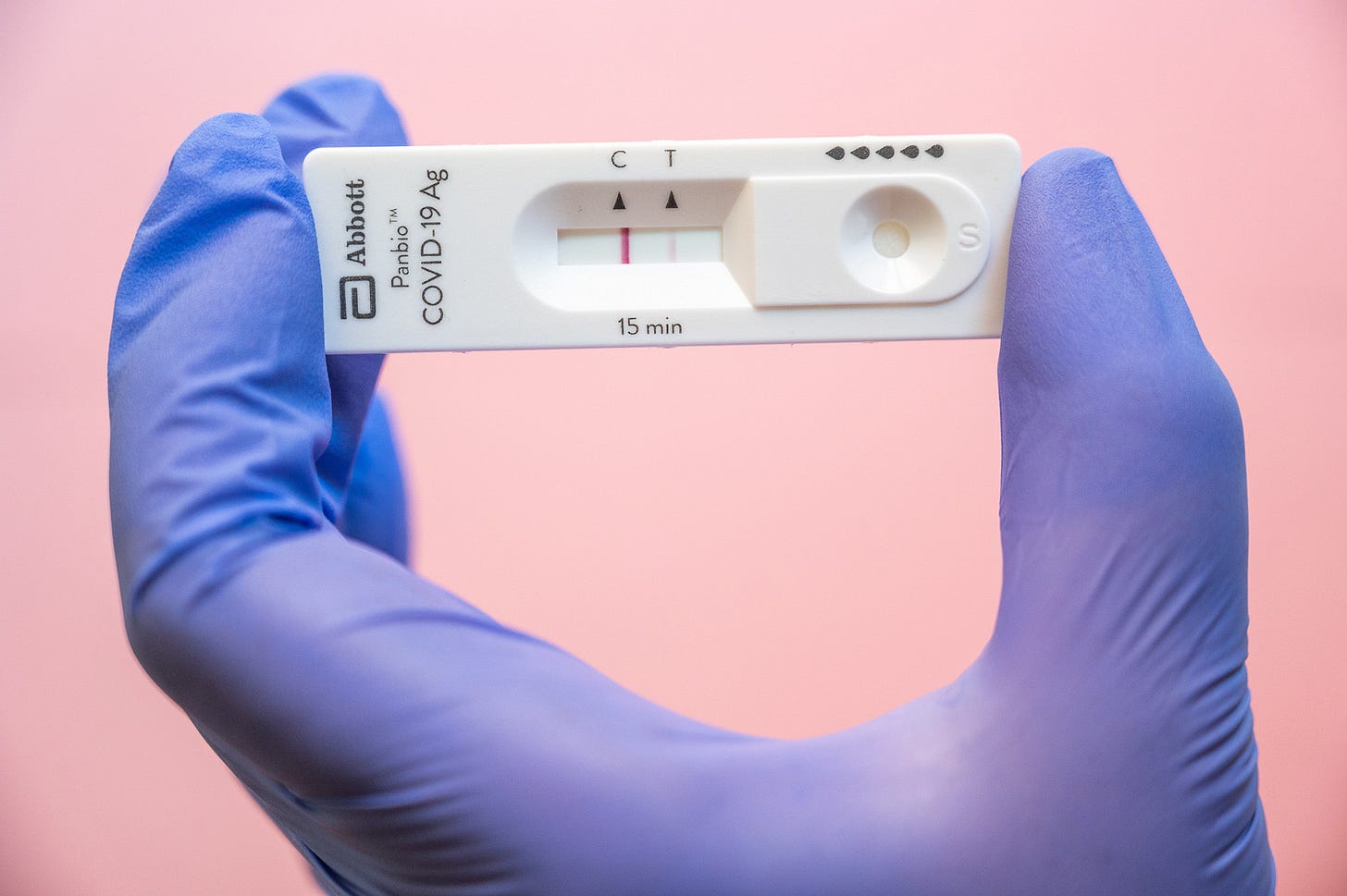

For a while I thought we might have just been wrong. Maybe dogs weren’t really as good at detecting COVID as we had thought. But an article recently popped up that made clear that the opposite was true: dogs are really good at detecting COVID, as good in fact as a PCR test (and much better than an antigen test). This wasn’t just a laboratory test either. Dogs could be trained in just a few weeks and were being used in a few places around the world: airports in Finland and Lebanon, a few schools in the US.

If dogs were so good at detecting COVID, why hadn’t they become mainstream, especially as we rushed to manufacture billions of single-use COVID tests? Researchers pointed to a lack of existing standards for scent dogs, around things like quality control. But when it came to the height of the pandemic, it wasn’t as though we had very good quality control in place anywhere nor were we unwilling to cut through red tape. After all, most of the CDC’s initial COVID tests were unusable and we threw hundreds of millions of dollars at testing companies that were functionally scams.

I argue the reason we never had dogs patrolling every airport, office, and school is more subtle: trust. Specifically, humans’ under-appreciated bias against sensory perception that differs from how we think about our own. Humans are visually-driven creatures, which doesn’t take a scientist to figure out. Aristotle’s hierarchy of the sense, some 2000 years ago, had vision at the top. We are best at seeing things and so we trust most when the thing we are trying to build trust in is something we can see.

It’s no wonder then that there are orders of magnitude more research on sight as well as on research that leverages sight as output compared to any other sense. When we want to detect cancer, we ask the question “what does cancer look like?” Biopsies today are our primary means of detecting cancer. Does cancer have a sound? Or a smell? If we had invested as much there as we have in trying to see cancer, would we be better off than where we are today? (In fact, cancer does seem to have smell and dogs have been shown to be capable of diagnosing cancer patients.)

We may be leaving so much on the table because we cannot get over the fact that our natural way of doing things may not be the best way in all cases. While this is troubling in itself, what is even more odious is that this historic bias becomes more and more self-perpetuating as our ability to explore via sight outstrips our research in other areas.

The Matthew effect states that advantage accumulates. In the context of science, this means it becomes easier (more funding, better instrumentation, best practices) to explore areas that are already well-established research topics. As a result, our belief that vision research yields the best results is very possibly self-fulfilling.

There is more research on vision because the available, present-day technology is better suited for studying vision than for studying other modalities. Although one may claim that vision is easier to investigate by nature, it seems quite likely that this claim and thus the technological advantage for vision is at least partially the result of a Matthew effect: As there is more research on and easier accessible technology for vision compared to other modalities today, there will most likely be more research on and technology for vision tomorrow.

We see this in action if we return to our COVID-sniffing dogs. We were able to (eventually) roll out widespread COVID tests because we had structures in place that made it easier to create, evaluate, and manufacturer tests that work by having you squint at a pink line. We created vaccines so quickly because we had already spent years investing in mRNA before COVID came along. But we had no existing infrastructure to support research and training around COVID-sniffing dogs because we’ve never trusted our (or any other animal’s) noses.

Since I am unlikely to alter the trajectory of all future scientific research, my most actionable conclusion is to recognize this bias towards sight in myself. Push back against the old adage “I’ll believe it when I see it.” When we smell smoke, our first reaction is to go looking for where the fire might be. Maybe instead we should trust our noses and just get out of the house.

[Looking back to last month]

Reflecting on Housing and Homelessness

Last month, I wrote about the intersection of affordable housing and homelessness. A number of readers reached out with interesting articles that added to that conversation. I encountered a few as well that added to my thinking.

This article articulates (better than I could) the same thesis that I landed on last month: homelessness is a housing problem. It specifically refutes the other leading hypotheses around causes of homelessness, which could be interesting to those not yet fully convinced of this thesis.

This compelling, interactive New York Times article shows the ways office buildings of different architectural can be converted to housing, some more easily than other. It expands on the Twitter thread I linked last month.

A Sandwich Shop, a Tent City and an American Crisis tells the story of a mom-and-pop sandwich store in Phoenix that is surrounded by one of the largest homeless encampments in the US. The grim, and at times gruesome, account articulates the feeling so many of us have that it feels like, when it comes to homelessness, there just aren’t any good options.

It has become a bit of a meme on “housing Twitter” (which I unsurprisingly find myself on) to post a picture of a beautiful and/or functional building that can’t be built in the US because of our building codes. This article argues of all our regulation, the primary driver of our banal architecture (besides our love of 5-over-1s) is our requirements around stairs.

[Misc]

Five Other Things

“Desert Hours” by Jane Miller: My late grandmother, who lived by herself in her Manhattan apartment until her passing at 91, would tell me about how she did at least one thing out of the house every day. “New York is the best place to be old,” she’d say, “and I can get anywhere in the city for $1.25. The bus drivers are all so nice to me.” Miller captures the same essence, weaving her daily routine through thoughts on aging, boredom, purpose, habit, and rules. My grandmother would have liked it.

I think quite a lot about dying and death, but I have very little to report on the subject, or at least nothing that my age could be said to have revealed to me. I find it impossible to believe that I will be dead fairly soon and not there to comment on the fact. That’s not because I fear it, but because I simply can’t imagine the world I know without me in it.

“Thinking Something Nice about Someone? Tell Them” by Derek Sivers: Sivers has been one of my favorite blogs for many years. He’s insightful but terse (the latter of which is a skill of his that I could certainly learn from). The concept of calling out the good things people have done and the impact they’ve had on you has been on my mind lately as well, and Sivers said it better than I could (so probably go read him instead of this). It’s one of the most under-leveraged super powers: everyone has it and it’s so easy to wield. I tweeted about this earlier this year:

“Hip-Hop at 50: An Elegy” by Jelani Cobb: Last year, I re-read one of my favorite books, Can't Stop, Won't Stop by Jeff Chang, about the history and politics of the “hip hop generation” (it’s a great read, especially the first 2/3rds, and is especially powerful as a “read then listen” by looking up the songs and artists he discusses, if that’s your sort of thing). In the year the Grammys pretty arbitrarily dubbed the 50th anniversary of hip-hop, Cobb examines the genre through the lens of death. Hip-hop is a genre foundationally shaped by death, both of its most influential artists and, through street violence, of so many of its earliest listeners.

There is, in this world, an ambivalent space reserved for revolutionaries who die in their beds and rappers who die of natural causes

The most beautiful surfing I’ve ever seen: Surfing has become my addiction in the past 2 years. Corey Colapinto, who is also a surfboard shaper and goes by the name Kookapinto, and his friend Jimmy Thompson create content that is everything I love about surfing: smooth, casual, free. Everyone I’ve shown them to, including people who have never had an inkling of interest in surfing, have been riveted. They’re like a meditation. Their videos have been so inspiring to me that I bought a Kookapinto board hoping it would help me capture just a little bit of how they surf (spoiler: it didn’t).

“The Case for Hanging Out” by Dan Kois: Technically a book review, this piece is anything but that (though Hanging Out: The Radical Power of Killing Time is now on my list). It’s really a narrative about hanging out that you’ll finish and think to yourself, “Damn, I need to be just hanging out more” (and you do). If you know me, you know I’m a hyper-extrovert. The “wanting to hang out” part comes easily to me. But in our world of over-planning and massive optionality, it’s hard to make time to just have time. One tip I read recently that I really liked is to find your friend group’s “default place” to hang out. The foundation of every “do nothing” sitcom is a default place for the group to hang out. In high school, you had someone’s basement. In college, you had that one friend’s dorm room. It’s similarly important to find that place in adult life: a friend’s apartment, a park, a bar, a cafe, or something else entirely. The Commons in San Francisco has become one of those places for me, where you can show up with no plan and know there will be interesting people to spend time with doing nothing in particular.

really appreciate your homelessness links! also sight bias brought me back to mcluhan, illiterate man has a more balanced sense ratio. also thought of how we can undeniably feel “vibes” but bc we cannot see them using an instrument, it is dismissed as quackery.

also did not know about aristotle’s hierarchy of sense so funny and fascinating

As always, interesting topics that inspire me to think outside my own space. There are also ideas here I’m currently interested in and these comments on them will make me dove deeper into the subjects. There’s a lot in this nicely curated, short blog!